The “Stolperstein” Project

“Stolpersteine” (“stumbling blocks”) are brass-plated cobblestones engraved with the names of victims of the National Socialist terror regime. Most of them had Jewish origins; others were victims of political persecution, members of the resistance, Sinti and Roma, Jehova’s Witnesses, homosexuals, or victims of euthanasia. The cobblestones measure 10 cm by 10 cm and are embedded in the sidewalk in front of the houses where each of the victims last lived, worked, or went to school by choice. In order to read the inscription, people need to lean forward, bowing to this tiny memorial for someone who in most cases has no grave. Conceived and realized by the Cologne artist Gunter Demnig, this “artistic memorial” continues to grow and cross borders; “Stolpersteine” are now found in many German towns and cities and a number of other countries.Almost 6,000 “Stolpersteine” have been placed in Berlin so far, over 2,500 of them in the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf borough alone. Family members, individuals, or groups initiate, apply for, and finance the installation; they also research and record the life stories of their “forgotten neighbors.”

The “Stolpersteine for Friedbergstrasse” initiative

In contrast to streets nearby, the first two “Stolpersteine” were placed at Friedbergstrasse 41 (on the initiative of one of the residents) only in April 2012. In June 2012, more than 20 residents of Friedbergstrasse started an initiative to research the fate of Jews who had lived on their street and had suffered humiliation, been deprived of their rights, and were excluded, persecuted, and driven to suicide or deported and murdered between 1933 and 1945.Friedbergstrasse – Steffeckstrasse – Friedbergstrasse

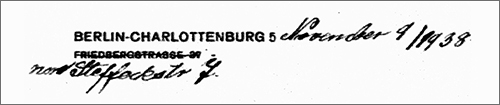

On July 30, 1897, “Street 18a of Dept. V” on the Charlottenburg land-use plan was named after the liberal jurist and politician Heinrich von Friedberg (1813-1895), a member of the Prussian Upper House (starting in 1872) and the Prussian minister of justice from 1879 to 1889.The National Socialists objected to Friedberg being honored this way, especially in light of his Jewish origins, and renamed the street Steffeckstrasse on September 17, 1938. The painter and graphic artist Carl Steffeck (1818-1890) had been well known for his historical paintings and portraits; one of his most famous paintings – “Albrecht Achilles im Kampf mit den Nürnbergern um eine Standarte” – was purchased by the Nationalgalerie.

Almost fifty years to the day after it was first named, Steffeckstrasse was renamed Friedbergstrasse on July 31, 1947. The houses on the “old” Friedbergstrasse were numbered consecutively from Leonhardtstrasse up to Suarezstrasse and then back, while Steffeckstrasse, as the street was called during the years of systematic deportations, had even numbers on one side of the street and odd numbers on the other. This numbering system was retained when the street was renamed Friedbergstrasse. In other words, the people who lived here had had several different addresses over the years, although they had lived in the same apartment for years or even decades. The people who fell victim to the Nazi terror regime had moved into Friedbergstrasse, were deported from Steffeckstrasse, and are now being remembered with a “Stolperstein” on Friedbergstrasse.

To avoid repeating this history of the street name in the life stories that follow, we use the houses’ current addresses throughout.

Preserving memory

Biographies of the people who are being commemorated on Friedbergstrasse with 23 (as of now) “Stolpersteine” have been put together on this website. Some of them are more detailed than others, since the research done in archives, memorial books, and databases, as well as the information provided by family members, produced widely varying results. Although the “Stolpersteine” were placed on November 10, 2013 – 75 years after the “Night of Broken Glass” – the “Stolpersteine for Friedbergstrasse” initiative will continue working to preserve memory.

“Stolperstein” installation on Friedbergstrasse

On November 10, 2013 – 75 years after the “Night of Broken Glass” in 1938 – nineteen “Stolpersteine,” or “stumbling blocks,” were placed on Friedbergstrasse and another fifteen on Suarezstrasse, as many neighbors and passersby looked on. The last Stolpersteine were installed where the two streets meet – at Friedbergstrasse 47 and Suarezstrasse 30 – with the help of everyone present. That concluded the “technical” part of the ceremony.

Photo 1: The stones are brought- © Carsten Molis

Photo 2: Placing the stones- © Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Photo 3: Keen interest - © Margit Robertz

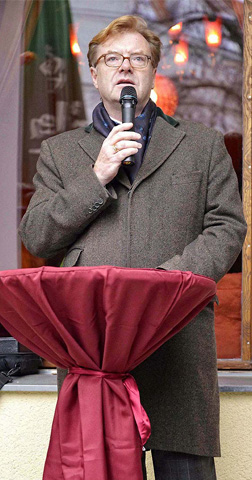

More than 200 people took part in a joint ceremony commemorating their former neighbors who had been murdered under the National Socialist regime. Gisela Morel-Tiemann spoke for the “Stolpersteine für die Friedbergstrasse” initiative, and Lothar Schaeffer for the Suarezstrasse initiative. André Schmitz, the Berlin Senate’s Permanent Secretary for Culture, spoke on behalf of the Senate and called the event a contribution to the Berlin “Diversity Destroyed” theme year, which was coming to a close.

Photo 1: The audience - © Carsten Molis

Photo 2: Gisela Morel-Tiemann - © Gregor Strick

Photo 3: Permanent Secretary André Schmitz - © Gregor Strick

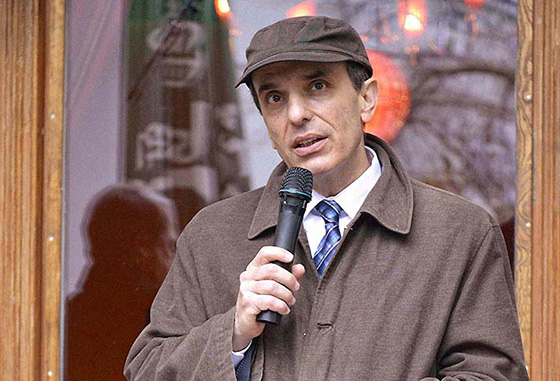

After speaking about the Holocaust and the significance of the Stolperstein project for the Jewish community as a whole, for the culture of memory in Germany, and especially in Berlin, Rabbi Daniel Alter said Kaddish for these people who have no grave.

Rabbi Daniel Alter - © Gregor Strick

Between the speeches, Gerold Gnausch played “Kol Nidrei” by Max Bruch and “Prayer from Jewish Life No. 1” by Ernest Bloch on the basset horn.

Both initiatives had hung posters with biographies of the victims around the site of the ceremony, so the people who were present had a chance to learn about their individual stories.

Biographies - © Carsten Molis

The biographies were also put up on the doors of the houses they had lived in so that passersby would be able to find out more about the fates of these victims of the National Socialist regime. In addition, the “Stolpersteine für die Friedbergstrasse” initiative distributed a brochure documenting the fates of the neighbors who were persecuted and murdered.

Following the joint ceremony, people went from one Stolperstein to the next, and each sponsor talked about the life of the person being commemorated at that site. White roses were laid at each Stolperstein, and candles were lit.

Photo 1: Biographies are read - © Martin Rheinsberg

Photo 2: Biographies are read - © Carsten Molis

Photo 3: Roses are laid- © Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Photo 4: Conversations after the speeches- © Petra Zimmerling

The speech by Svea Blumenthal from Stuttgart about her great-aunt and great-uncle – Vera and Rudolf Blumenthal – in front of Friedbergstrasse 14 was especially moving. Her parents, Heidi and Joachim Blumenthal, had also come from Hamburg to commemorate these members of their family.

After the Stolpersteine were laid and the commemorative event was over (which lasted from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.), around 80 of the participants met at a restaurant to talk about their impressions and feelings.

Candles in the night - © Carsten Molis

As evening fell, Friedbergstrasse took on a new atmosphere: candles illuminated the Stolpersteine, and many passersby stopped in front of the individual houses to read the biographies hung on the door and the inscriptions on the Stolpersteine. In order to read these inscriptions, they had to bow to these memorials for people who had been persecuted and murdered or driven to suicide solely because they were Jewish – and who had never imagined that they could be shut out of their German homeland and nationality, driven from their homes, and killed.

On March 24, 2014, the artist Gunter Demnig personally installed two more Stolpersteine in front of Friedbergstrasse 34, for Lane Grünebaum and Max Stern.

Gunter Demnig at Friedbergstrasse 34 - © Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Stolpersteine on Friedbergstrasse in Berlin-Charlottenburg now (as of April 2014) recall 23 people who fell victim to the National Socialist regime and racial ideology.

Today, their fate admonishes us to oppose discrimination of all kinds, to stand by people who are being shut out and persecuted for their faith, their origins, or their political opinions, and to help them achieve a self-determined life in freedom and equality.

Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Installation speech, Friedbergstrasse,

November 10, 2013

Ladies and gentlemen,

Thank you for coming to Friedbergstrasse and Suarezstrasse today – 75 years after the “Night of Broken Glass” – to remember the people who were deported and sent to their deaths from right here.

My name is Gisela Morel-Tiemann, and I would like to welcome you on behalf of both “Stolperstein” initiatives. I especially want to welcome the members of the Blumenthal family who have come to Berlin to remember Vera and Rudolf Blumenthal, who – like so many others in their family – were killed by the Nazi regime. Svea Blumenthal will tell you more about their lives as we visit the individual “Stolpersteine.”

Rabbi Alter, we would like to thank you for speaking to us today and for saying Kaddish for these people who have no grave. Thank you to you, too, Mr. Gnausch, for giving our ceremony an appropriate and moving musical framework. We would also like to thank you, Permanent Secretary Schmitz, for taking time out of your busy schedule to come here and for bringing us the best wishes of the Senate.

Now we want to turn our attention to the people whose lives were taken. They are the reason we are here today.

In the summer of last year, more than 20 people who live on Friedbergstrasse set up an initiative to research the fate of 21 former neighbors who had fallen victim to National Socialist racial ideology. Many of us belong to the generation that grew up with parents and grandparents who never spoke about those years. That may have been one reason why we decided to devote our energy, either professionally or privately, to investigating the darkest chapter of German history.

We knew that researching the lives of those who were deported would be an emotional task. Six million is a number that is hard to imagine. When you’re researching the life of one person, however – and the horrifying way they died – you almost feel as though you know them personally. And that person’s life is something you can imagine, especially when he or she lived on your street or maybe even in your house.

The systematic murder of people who had a deep bond with their German fatherland, who simply wanted to live and who couldn’t believe they would be shut out and then murdered, and of people who defied Hitler’s insanity, is something that shocks and appalls us.

We were relatively prepared for the horror of what we would find in the archives. And yet the inhuman, bureaucratic language of the files and their meticulous detail was deeply unsettling.

We were almost elated by each new discovery of someone who had managed to escape the Nazis – at the same time, however, we knew that being driven into exile and being separated from family and friends is an unhappy fate. Often we felt like voyeurs, and were profoundly shaken by what we read or what we heard from survivors.

The postwar files held their own examples of linguistic missteps and appalling bureaucracy. For example, the children of a woman who was murdered in Auschwitz received 150 marks a month as “Entschädigung” (damages) for what their mother had suffered before her death. “Entschädigung” – or even worse, “Wiedergutmachung” (compensation) – what kind of language is that? The state-decreed murder of human beings cannot be “entschädigt” oder “wiedergutgemacht.” All one can do is to ask humbly for forgiveness and preserve and pass on the memory of what happened.

Those of us born afterwards are of course not responsible for the crimes that Germans committed, approved of, or at least tolerated and often later denied. But we are responsible for ensuring that they are not forgotten.

We are responsible for the present, for what happens today and for what we allow to happen. Newspapers report almost every day on discrimination and threats against victims of political persecution or on war refugees seeking asylum in Germany. Erich Kästner, who lived here in Charlottenburg, whose books were burned, who was harassed – but who survived the Third Reich here in Germany – once said that people who fail to prevent wrongdoing are just as guilty as the perpetrators.

We cannot look away and keep silent when people are in desperate straits, when they are the victims of injustice, or are even threatened and attacked – for whatever reason. And anti-Semitism is still one of those reasons, even today. We cannot close our eyes; we have to speak up, offer our help, and take responsibility. The cruel fate of the people we are remembering with “Stolpersteine” exhorts us to do that.

After the ceremony, you will hear more about the lives of our formerly “forgotten neighbors” as we go from one “Stolperstein” to another. The brochures, which you are welcome to take with you and to give to others, will tell you something about the idea behind the Cologne artist Gunter Demnig’s “Stolperstein” memorials, which we are contributing to today. You will read about what happened on Friedbergstrasse – as well as everywhere in Germany and elsewhere, too – and about what people allegedly didn’t see and didn’t know about. You will be moved when you read that help was given in only a single case and that it enabled an entire family to escape. In other cases, however, people enriched themselves at the expense of their former neighbors.

We plan to continue our commemorative work and will post new information on this website when we have it.

Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Friedbergstrasse 1

Pauline Kallmann

Pauline Kallmann, née Schneler, was born on May 9, 1871, in Schmolsin (Stolp district) in Pomerania. She had lived in a two-room apartment in the front part of Friedbergstrasse 1 (second floor, on the left) since 1911. Mrs. Kallmann was widowed and had no children. She was Jewish.

She was a 71-year-old retiree when she was deported by the Nazis on January 13, 1942, from the Grunewald freight station, Platform 17, on the train 8 Da 44 to Riga. Detailed records still exist showing how the National Socialist authorities confiscated Pauline Kallmann’s apartment on Friedbergstrasse after her deportation, as well as her assets, and sold her furniture and personal effects.

Her fate after that is still unclear. However, we do know that starting in the winter of 1941/1942, the people deported to Riga by the Nazis were crowded into unheated cattle cars, and many of them died along the way. Because of her age, Pauline Kallmann was probably one of the people who were either murdered right after their arrival in Riga or shot and buried in Bikernieki Forest after the mass “selections” that took place in the Riga ghetto in February and March 1942.

Research and text: Caroline Kitzerow, Carsten Molis

Friedbergstrasse 7

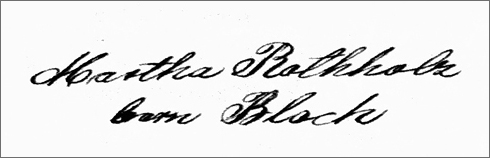

Martha Rothholz

Martha Rothholz was from Posen and was born on October 17, 1875, as the oldest daughter of the rabbi and historian Dr. Philipp Bloch and his wife Luise, née Feust. After attending a girls’ school and a teacher training college, she took the teacher certification examination, but spent her life as a housewife.

On October 16, 1898, she married Dr. Julius Rothholz. In 1901, the two of them bought the house at Friedbergstrasse 7 with Martha’s dowry. The couple had three children – Bertha (1900–1993), Alfred (1903–1994), and Therese (1906–1943) – and four grandchildren. In 1939, Alfred managed to escape to New York with his wife Käthe and daughter Luisa, where he – although he had been an engineer in Germany – was only able to work as a mechanic.

Therese, her husband Franz Joseph Unger, and their son Heinz Joachim were murdered in 1943 in Auschwitz and Sobibor. Bertha’s husband Max Platschek, the owner of a garment factory, was supposed to have been arrested and sent to a concentration camp in connection with the “Night of Broken Glass” in November 1938, but Julius Rothholz was warned in advance by friends, and he helped his daughter Bertha, her husband, and their two sons, Hans and Karl, to escape.

Dr. Julius Rothholz committed suicide on February 2, 1939, in order to avoid being arrested by the Gestapo.

Martha Rothholz’s not inconsiderable fortune was confiscated, as was the house at Friedbergstrasse 7. Starting in September 1941, she, like so many others, was forced to wear the yellow star. On November 27, 1941, the Nazis deported Martha Rothholz to Riga, along with around 730 other Jews from Berlin. She was shot to death on the morning of November 30, 1941.

Bertha Platschek and her family were able to start a new life in Montevideo, Uruguay. Her son Karl became a successful engineer in Venezuela and the United States, while her son Hans returned to Germany in 1953 and made a name for himself as a painter and a writer.

Research and text: Gregor Strick

Dr. Julius Rothholz

Dr. Julius Rothholz was from Schwersenz, near Posen, and was born on December 6, 1864. His father was a tradesman.

Julius Rothholz studied mathematics, statistics, and economics at university and earned a doctorate for his study on Fermat’s theorem (Giessen, 1892). He worked as a teacher until being hired as a statistician in Berlin’s state insurance agency in 1898, where he eventually became the head of the statistics department. He published many different articles on statistics (e.g., “Die deutschen Juden in Zahl und Bild” (German Jews in Numbers and Images, Berlin, 1925). He was awarded the Red Cross Medal and the Merit Cross for his work as a member of the city council and the guardianship council and as one of the founders of an organization that helped people find employment.

On October 16, 1898, he married Martha Bloch. In 1901, the two of them bought the house at Friedbergstrasse 7 with Martha’s dowry. The couple had three children – Bertha (1900–1993), Alfred (1903–1994), and Therese (1906–1943) – and four grandchildren. In 1939, Alfred managed to escape to New York with his wife Käthe and daughter Luisa, where he – although he had been an engineer in Germany – was only able to work as a mechanic.

Therese, her husband Franz Joseph Unger, and their son Heinz Joachim were murdered in 1943 in Auschwitz and Sobibor. Bertha’s husband Max Platschek, the owner of a garment factory, was supposed to have been arrested and sent to a concentration camp in connection with the “Night of Broken Glass” in November 1938, but Julius Rothholz was warned in advance by friends, and he helped his daughter Bertha, her husband, and their two sons, Hans and Karl, to escape.

Dr. Julius Rothholz committed suicide on February 2, 1939, in order to avoid being arrested by the Gestapo.

Bertha Platschek and her family were able to start a new life in Montevideo, Uruguay. Her son Karl became a successful engineer in Venezuela and the United States, while her son Hans returned to Germany in 1953 and made a name for himself as a painter and a writer.

Research and text: Gregor Strick

Therese Unger

Therese Felicia Rothholz was the youngest child – after her sister Bertha and her brother Alfred – of Martha and Julius Rothholz and was born on March 23, 1906, in Berlin. We do not know whether she learned a profession, but she spoke fluent English, as well as Spanish. Therese Rothholz married Franz Joseph Unger, who was born on April 27, 1899, in Schrimm (in the Prussian province of Posen) as the youngest son of Siegmund and Johanna Unger. Franz Joseph Unger was a mechanical engineer and had become the joint owner of a wholesale business in Berlin in 1924. Their only child, Heinz Joachim, was born on September 26, 1928.

In 1930 Therese and Franz Joseph Unger went into business for themselves with a laundry in Charlottenburg, at Leonhardtstrasse 20, and one in Halensee, at Johann-Georgstrasse 10. Both laundries were completely destroyed in the “Night of Broken Glass” in 1938 and could not be reopened. After that, Therese and Franz Joseph Unger worked as sales clerks – she at Kaufhaus des Westens and her husband at Karstadt in Neukölln.

They planned to emigrate to Chile or Bolivia with their little boy and were able to get visas. However, Franz Joseph Unger had paid the middleman with stocks and foreign currency he had not declared in the statement on assets that all Jews were required to submit, for which he was arrested at the beginning of 1939 and sentenced to eight months in prison in Plötzensee. After his release on September 30, 1939, he was put to work as a welder on road construction, while Therese Unger was ordered into forced labor in a factory.

They were unable to leave for Bolivia or Chile, since both countries were now refusing entry to Jews. The Ungers decided to send their eleven-year-old son to the Netherlands on a “Kindertransport,” a train taking Jewish children to supposed safety, and moved in with Therese’s mother, Martha Rothholz, at Friedbergstrasse 7. After Martha Rothholz was deported at the end of 1941, the house was confiscated and the Ungers were evicted and sent to live at Spandauer strasse 17 (today called Spandauer Damm).

In an operation on February 27, 1943, known as the “factory action,” the last approximately 11,000 Jews still living in Berlin – most of whom were forced laborers in arms factories or Jewish spouses of “Aryans” who had so far been spared – were arrested at their workplace in mass raids. Therese and Franz Joseph Unger were among those arrested that day.

Therese Unger was deported to Auschwitz on March 2, 1943, along with 1,755 others, from the Moabit freight station on Putlitzstrasse with the 32nd “Osttransport.”

She was just 38 years old at the time. She apparently first did forced labor in the Monowitz labor camp near Auschwitz. Her husband was among the 1,726 people who were sent to almost certain death one day later on the 33rd “Osttransport” to Auschwitz; a letter he wrote to his sister shows that he worked at the Monowitz camp in April 1943.

Therese Unger and her husband were murdered in Auschwitz.

Research and text: Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Franz Joseph Unger

Franz Joseph Unger was born as the youngest son of Siegmund Unger and his wife Johanna, née Silberstein, on April 27, 1899, in Schrimm in the Prussian province of Posen. After completing school and studying mechanical engineering in Bochum, he became the joint owner of a wholesale business in Berlin in 1924. He married Therese Felicia Rothholz, who was born in Berlin on March 23, 1906, as the youngest child of Martha and Julius Rothholz. Their only child, Heinz Joachim, was born on September 26, 1928.

In 1930 Therese and Franz Joseph Unger went into business for themselves with a laundry in Charlottenburg, at Leonhardtstrasse 20, and one in Halensee, at Johann-Georgstrasse 10. Both laundries were completely destroyed in the “Night of Broken Glass” in 1938 and could not be reopened. After that, Franz Joseph Unger worked as a sales clerk at Karstadt in Neukölln and his wife at Kaufhaus des Westens.

They wanted to emigrate to Chile or Bolivia and were able to get visas. However, Franz Joseph Unger had paid the middleman with stocks and foreign currency he had not declared in the statement on assets that all Jews were required to submit, for which he was arrested at the beginning of 1939 and sentenced to eight months in prison in Plötzensee. After his release on September 30, 1939, he was put to work as a welder on road construction, while Therese Unger was ordered into forced labor in a factory.

They were unable to leave for Bolivia or Chile, since both countries were now refusing entry to Jews. The Ungers decided to send their eleven-year-old son to the Netherlands on a “Kindertransport,” a train taking Jewish children to supposed safety, and moved in with Therese’s mother, Martha Rothholz, at Friedbergstrasse 7. After Martha Rothholz was deported at the end of 1941, the house was confiscated and the Ungers were evicted and sent to live at Spandauer strasse 17 (today called Spandauer Damm).

On January 13, 1943, Franz Joseph Unger and Gertrud Aronsfeld, née Unger, wrote to their sister Herta Platschek in Stockholm that they anticipated being deported any day now. In an operation on February 27, 1943, known as the “factory action,” the last approximately 11,000 Jews still living in Berlin – most of whom were forced laborers in arms factories or Jewish spouses of “Aryans” who had so far been spared – were arrested at their workplaces in mass raids. Therese and Franz Joseph Unger were among those arrested that day.

Franz Joseph Unger was deported to Auschwitz on March 3, 1943, along with 1,725 others, from the Moabit freight station on Putlitzstrasse with the 33rd “Osttransport.”

His wife shared the same fate a day earlier.

Franz Joseph Unger was last heard from when his sister Frieda Flüchter, who was married to a non-Jewish man in Westphalia, giving her a degree of protection, received a letter from him in April 1943 from the Monowitz labor camp near Auschwitz. He wrote that he had “moved away” from Berlin, he was doing well, he was healthy and in good spirits, and he was able to work in his profession.

Franz Joseph Unger and his wife were murdered in Auschwitz.

Research and text: Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Heinz Joachim Unger

Heinz Joachim Unger was born on September 26, 1928, as the only child of Franz Joseph and Therese Unger, née Rothholz, in Berlin. Since both of his parents worked, he lived with his grandparents, Martha and Julius Rothholz, at Friedbergstrasse 7 during the week, starting when he was five years old.

His grandmother called him a “charming child” and a “sweet-bird,” whom she loved with all her heart, in a letter she wrote on November 9, 1938. That was the night that synagogues were torched, Jewish-owned shops were plundered and destroyed, and many Jews were beaten, killed, or arrested in Germany, Austria, and occupied Czechoslovakia. With her letter, Martha Rothholz tried but failed to get an affidavit from a distant, very prominent relative in the U.S. that would enable Heinz Joachim Unger and his parents to emigrate. These notarized guarantees of support were a prerequisite for entering the U.S. and several other countries.

Only ten years old at the time, Heinz Joachim suffered the complete destruction of his parents’ laundries during the “Night of Broken Glass,” the departure overnight of a number of close family members, and the suicide of his beloved grandfather, who had helped his oldest daughter, Bertha, and her family to flee and knew it was only a matter of time before he was arrested by the Gestapo.

Therese and Franz Joseph Unger decided to save their son by putting him on a “Kindertransport,” a train taking Jewish children to the Netherlands, especially since they knew they were being watched by the Gestapo. At the end of 1938, Heinz Joachim arrived in the Netherlands and was put into foster care in Amsterdam with a family named Pelz. Since no one knew whether his parents could afford to pay for his care, he was sent to Eindhoven on January 5, 1939, to the “Dommelhuis,” which took in refugee boys for a time. He then moved in with the E. Vecht family at Hugo de Grootstraat 104 in Rotterdam on August 16, 1939.

The street they lived on was a mixed industrial and residential area that was reduced to rubble when it was bombed on May 14, 1940, shortly after the German army invaded the Netherlands. The Vechts’ home was destroyed; we do not know whether they even survived the bombing.

Since Heinz Joachim Unger was being treated for a broken leg at the Israelite Orphanage at Mathenesserlaan 208 in Rotterdam at the time, the Control Commission for Jewish Refugee Children in Foster Care asked the orphanage to keep him there.

On October 8, 1942, Heinz Joachim Unger – along with all the other refugee children from Germany and Austria living in the orphanage – was sent to the Westerbork transit camp. The trip to Westerbork, which was about 200 kilometers away, apparently took two days, since October 10 is given as the date of the children’s arrival in the camp. He was first housed in Barrack 21, spent a few days in the camp hospital in February 1943, and was then moved to Barack 35, the camp orphanage.

Heinz Joachim Unger was transported to the death camp Sobibor on April 13, 1943, where he and many others were murdered in the gas chamber shortly after their arrival on April 16, 1943.

He was only fourteen and a half when he died, and his carefree, happy life as a sheltered, much-loved child had ended when he was ten years old.

Research and text: Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Gertrud Aronsfeld

Gertrud Aronsfeld was born on October 16, 1889, in Schrimm, in the Prussian province of Posen, as the oldest child of Siegmund Unger and his wife Johanna, née Silberstein.

Her sister Frieda was born in 1890, her sister Herta in 1892, and her brother Franz Joseph in 1899. Shortly after finishing school, Gertrud Unger met Dr. Heimann Aronsfeld, a devoutly religious doctor and obstetrician (1865-1934). After marrying in 1910, the couple lived in nearby Kruschwitz, where their five children were born (two of whom died shortly after birth). Gertrud Aronsfeld was a mother and a housewife.

When the province of Posen was given to the restored Polish state in 1919, Heimann Aronsfeld was told he would have to repeat his licensing examination in order to practice medicine – this time in Polish. He refused, and he and his wife left their home in 1922 and moved to Berlin, where both of them had siblings, with their children Eva (born on April 22, 1916), Susi (born on May 18, 1917), and Curt (born on November 18, 1920).

The Aronsfeld family could not find an apartment and was also unable to stay with Heimann’s brothers, Alex Aronsfeld at Dahlmannstrasse 15 and David Aronsfeld at Gleditschstrasse 31, or with Gertrud’s brother, Franz Joseph Unger. (Both Alex and David Aronsfeld were able to flee Germany with their families in 1938/1939.)

Gertrud and Heimann Aronsfeld moved into a hotel with two-year-old Curt, while the girls – Eva and Susi – lived with friends of the family, who were well-to-do and childless. In 1924 Dr. Aronsfeld opened a medical practice at Bülowstrasse 31, where he and his wife and son also lived. Their daughters stayed with the family’s friends, who soon took in Curt as well. Dr. Aronsfeld died of cancer on February 4, 1934, and was buried secretly at night in the Adass Jisroel cemetery in Berlin-Weissensee, since Jews had already been forbidden to hold formal burials and to mark graves with a tombstone.

Back then, Gertrud Aronsfeld had very little contact with her brother Franz Joseph in Berlin and none at all with her sister Frieda, who lived in Westphalia with her non-Jewish husband, since the Adass Jisroel congregation avoided interaction with non-Orthodox Jews and rejected “mixed marriages” on principle.

Eva Aronsfeld wanted to become a doctor, but had to leave school in 1933, the year before she would have graduated, because she was Jewish. She worked for Keren Hayesod at Meinekestrasse 10, a Zionist organization that supported Jewish emigration to Palestine and helped with arrangements for emigration. With her connections, she was able to get her brother out of Germany within 24 hours and into London, where he – married, but childless – died at the age of 60. Eva herself emigrated to London in March 1939, where she died relatively young and unmarried.

In mid-1938 Gertrud Aronsfeld gave up six rooms of her boarding house to Jewish neighbors who rented out rooms in the same house, since she wanted to emigrate either to England to be with her son or to Sweden to her sister Herta. Both countries refused to give her a visa. In April 1939 – after her daughter Eva had emigrated – she “sold” her boarding house to the neighbors (who were later deported themselves) and moved to Dahlmannstrasse 15 with her daughter Susi. Gertrud’s brother-in-law Alex Aronsfeld had lived at the same address with his non-Jewish wife, Anna, before emigrating; Anna Aronsfeld moved to Niebuhrstrasse 68 after her husband left Germany.

Susi Aronsfeld had also been forced to leave school and worked at the Palestine Trust and Transfer Company, which helped Jews to emigrate to Palestine. There she met Heinz Bluth, who was from Erfurt and, as a Jew, had lost his managerial position at a bank in Berlin. Together they fled Berlin on October 13, 1939, for Palestine and, after months of anxiety, afraid that they would never reach their destination, living without papers and in fear of discovery, they arrived in Haifa on January 30, 1940. They married a short time later, and their son Michael was born in 1946.

After her children had left, Gertrud Aronsfeld was alone in Berlin. She moved in with Martha Rothholz, the mother-in-law of her brother Franz Joseph Unger, as a boarder at Friedbergstrasse 7, where her brother, his wife Therese, and their son Heinz Joachim were already living. After Martha Rothholz was deported in November 1941, the house was confiscated and its residents were evicted. Gertrud Aronsfeld had to move to Dahlmannstrasse 4, which was probably a “Judenwohnung” (Jewish apartment).

On January 21, 1943, Gertrud Aronsfeld was taken to the Moabit freight station on Putlitzstrasse and deported with almost 2,000 other Jews from Berlin on the 26th “Osttransport” to Auschwitz, where she was murdered.

Her daughter Susi Bluth-Aronsfeld in Israel was very glad to hear that her mother was going to be remembered with a “Stolperstein.” With her alert mind, prodigious memory, and willingness to answer all of our questions, she was a great help with our research. Unfortunately, she died on August 28, 2013, before the “Stolperstein” for her mother, Gertrud Aronsfeld, was laid.

Research and text: Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Friedbergstrasse 10

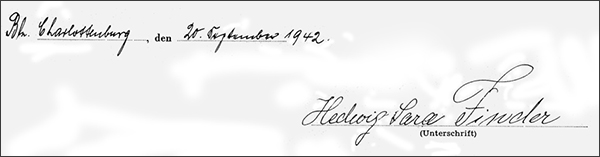

Hedwig Finder

Hedwig Finder was born on August 2, 1876, in Posen as Hedwig Loewy. She was the widow of Felix Finder and last worked as a home health nurse for 70 reichspfennig an hour. Since 1934, she had sublet an apartment on the fifth floor of the front house of Friedbergstrasse 10 from Benno Loewy, who was also born in Posen (on February 14, 1879). Benno Loewy was first listed in the “Jewish Address Book” as a tradesman and later, after 1933, as a decorator. He survived the Third Reich, probably thanks to his non-Jewish wife Frieda, and remained in Charlottenburg after the war.

Hedwig Finder and Benno Loewy were brother and sister.

What is known is that Hedwig Finder was deported on September 26, 1942, from the Moabit freight station on Putlitzstrasse with 1,042 other victims, including many families with small children, on the 20th “Osttransport.” Three hundred Jews from Frankfurt/Main were added to this group. Hedwig Finder is listed on the train’s manifest as number 256 and classified as unable to work.

The train’s original destination was the Riga ghetto, but the ghetto was already overcrowded. Shortly after arriving at the train station in Raasiku, 29 kilometers east of Tallinn, women, children, and people who were either older or sick were put on busses and taken to the sand dunes along the Baltic Sea near Kalevi-Liiva, where they were shot by a German-Estonian commando. Hedwig Finder was 66 years old.

Six weeks after Hedwig Finder’s deportation, her apartment on Friedbergstrasse was cleared out and her personal effects, a sewing table, a sewing machine, and a suitcase containing her clothes, were confiscated and sold to the head of the Wehrmachtsfürsorge (armed forces welfare agency) for 60 reichsmarks.

Research and text: Magdalena Kemper

Friedbergstrasse 14

Vera Blumenthal

Vera Blumenthal, née Senger, was born on September 10, 1899, in Köslin in the Prussian province of Pomerania as the daughter of the tradesman Louis Senger and his wife Anna, née Lewin. Her brother Ernst, who was able to emigrate to America via Shanghai after 1933, was born on September 4, 1902.

In July 1925, Vera Senger married Rudolf Blumenthal, who was from Berlin and had a degree in engineering, and moved to Charlottenburg with him. They first lived on Utrechter strasse. After 1935, the Blumenthals had two addresses, Leonhardtstrasse 4 and Friedbergstrasse 5, one of which was probably their home and the other Rudolf Blumenthal’s office. In 1940, they moved into a four-room apartment at Friedbergstrasse 14. The inventory list made later when the apartment was cleared out suggests that Rudolf Blumenthal also had his office here. The couple had no children, and Vera Blumenthal ran what was probably an upper-middle-class household.

Photo: Property of the Blumenthal family; back row (from left to right): Heinrich Blumenthal, sister, Else (wife of Leopold), Rudolf and Vera Blumenthal, Leopold Blumenthal; front row (from left to right): Rosa Beer, Louis Blumenthal, Margarete Blumenthal (wife of Heinrich) with her son Klaus

Vera Blumenthal and her husband were taken from Friedbergstrasse 14 and deported to Riga on October 26, 1942, with the 22nd “Osttransport,” along with 800 others. More than 500 of the people sent to their deaths on this train were members of the board and employees of the “Jüdische Kultusvereinigung Berlin” (Jewish Religious Society), the successor to the Jewish Community Berlin, which had been deprived of its legal status by the Nazis. They and their families had been arrested on October 20, 1942 , during what was called the “community action” and detained at the Levetzowstrasse collection camp. The Nazis wanted to weaken Berlin’s Jewish community, and these mass arrests dealt a severe blow: the community lost almost all of its leadership and more than a third of the staff.

The Blumenthals’ apartment was cleared out and their assets confiscated in January 1943. Unbelievably, their landlady sued for “back rent” owed from the time the Blumenthals were deported in October 1942 to the time the apartment was cleared out in January 1943, as well as for renovations, although she had sublet the Blumenthals’ beautifully furnished apartment –with all of their possessions – from November to January to other tenants. She won her case.

Vera Blumenthal and her husband Rudolf were murdered shortly after arriving in Riga on October 29, 1942.

Research and text: Simon Dankou, Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Rudolf Blumenthal

Rudolf Blumenthal was born in Berlin on May 27, 1894, as the third child of Louis Blumenthal (1862-1940) and his wife Martha, née Beer (1859-1908), both of whom were from Pomerania.

Photo: Property of the Blumenthal family, back row: Leopold Blumenthal, front row (left to right): Heinrich, sister und Rudolf Blumenthal

Rudolf Blumenthal had an older brother, Leopold (1888-1943, probably suicide), an older sister, and a younger brother, Heinrich (born 1896 in Berlin; murdered in Auschwitz on December 31, 1944). Martha Blumenthal died in 1908, when her four children were still underage. Her sister, Rosa Beer (who died in Theresienstadt on March 4, 1943) took care of her niece and three nephews after their mother’s death.

Rudolf Blumenthal went to college and became an engineer. In July 1925, he married Vera Senger, who was born on September 10, 1899, in Köslin (in the Prussian province of Pomerania) as the daughter of the tradesman Louis Senger and his wife Anna, née Lewin, and moved to Charlottenburg with her. They first lived on Utrechter strasse. After 1935, the Blumenthals had two addresses, Leonhardtstrasse 4 and Friedbergstrasse 5, one of which was probably their home and the other Rudolf Blumenthal’s office. In 1940, they moved into a four-room apartment at Friedbergstrasse 14. The inventory list made later when the apartment was cleared out suggests that Rudolf Blumenthal also had his office here. The couple had no children, and Vera Blumenthal ran what was probably an upper-middle-class household.

Rudolf Blumenthal and his wife were taken from Friedbergstrasse 14 and deported to Riga on October 26, 1942, with the 22nd “Osttransport,” along with 800 others. The victims also included Rudolf’s cousin, Richard Blumenthal (1906–1942), his wife Liselotte, née Samuel (1914–1942), and their daughter Tana (1941–1942).

The Blumenthals’ apartment was cleared out and their assets confiscated in January 1943. Unbelievably, their landlady sued for “back rent” owed from the time the Blumenthals were deported in October 1942 to the time the apartment was cleared out in January 1943, as well as for renovations, although she had sublet the Blumenthals’ beautifully furnished apartment – with all of their possessions – from November to January to other tenants. She won her case.

Rudolf Blumenthal and his wife Vera were murdered shortly after arriving in Riga on October 29, 1942.

Research and text: Simon Dankou, Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Friedbergstrasse 26

Hildegard Levy

Hildegard Levy was born in Berlin on June 5, 1899, as the daughter of Carl Levy, who was from Eastern Pomerania, and his wife Hulda, née Phiebig. Hildegard Levy’s father had owned the house at Friedbergstrasse 26 since 1910, and she lived there with him in what – for the owner of an apartment building – was a rather modest three-room apartment. She also owned a weekend property at Hohengatow with a small cottage. Nothing is known about the life of her deceased mother, Hulda Levy.

As a result of the “Gesetz über die Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums” (Civil Service Restoration Act) of April 7, 1933, Hildegard Levy lost her job as a civil servant in Berlin. In 1941, she was a forced laborer for OSRAM, which manufactured products essential to the war effort.

Her father had run a small factory that made buttons, belts, and buckles at Friedbergstrasse 26 since about 1913, but was forced to close it in 1938 as a result of the “Aryanization” and liquidation of the Berlin clothing manufacturers located mostly at Hausvogteiplatz, many of which had Jewish owners. And because Jews were required to pay a special tax on their assets after the “Night of Broken Glass” and a “tax for fleeing the Reich” (“Reichsfluchtsteuer”), Carl Levy had to come up with a considerable sum for the Tax Office. In order to do so, he had to pawn securities and sell his house in 1939 for less than it was worth.

Shortly before Hildegard Levy and her father Carl were deported, their entire assets were “confiscated for the benefit of the German Reich” by an order of the Gestapo of October 3, 1941: their bank accounts, the remaining securities, and all of their household goods.

Hildegard Levy and her father were deported to the Litzmannstadt ghetto on October 27, 1941. The actual date on which they were murdered is unknown.

Research and text: Prof. Tine Stein, Jan Lange

Carl Levy

Carl Levy was born on September 26, 1867, in Zachan, Eastern Pomerania. He had owned the house at Friedbergstrasse 26 since 1910. He lived there with his daughter Hildegard, who was born in Berlin on June 5, 1899, in what – for the owner of an apartment building – was a rather modest three-room apartment. Nothing is known about the life of his deceased wife, Hulda Levy, née Phiebig.

Since about 1913, Carl Levy had run a small factory at Friedbergstrasse 26 that made buttons, belts, and buckles for the Berlin clothing manufacturers located mostly at Hausvogteiplatz, many of which had Jewish owners. He was forced to close it in 1938 as a result of the “Aryanization” and liquidation of these businesses. His daughter Hildegard had already lost her job as a civil servant in Berlin as a result of the “Gesetz über die Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums” (Civil Service Restoration Act) of April 7, 1933.

Because Jews were required to pay a special tax on their assets after the “Night of Broken Glass,” Carl Levy had to come up with a considerable sum for the Tax Office. He was also required to pay a “tax for fleeing the Reich” (“Reichsfluchtsteuer”), which had been imposed on most of the Jews subject to property taxes since 1938/1939, regardless of whether they were planning to emigrate or not. Berlin’s Tax Offices had come up with this policy on their own, as part of the increasingly drastic measures applied to Jews. In order to make these payments, Carl Levy had to pawn securities and sell his house in 1939 for less than it was worth. After the war, the Federal Republic of Germany recognized the claim of the Levys’ heirs to the property at Friedbergstrasse 26, although they were required to reimburse the buyers who had purchased it in 1939.

Shortly before Carl Levy and his daughter Hildegard were deported, their entire assets were “confiscated for the benefit of the German Reich” by an order of the Gestapo of October 3, 1941: their bank accounts, the remaining securities, and all of their household goods.

Carl Levy and his daughter Hildegard were deported to the Litzmannstadt ghetto on October 27, 1941. The actual date on which they were murdered is unknown.

Research and text: Prof. Tine Stein, Jan Lange

Feige Rebensaft

Feige Rebensaft, née Przemyslaner, was born on May 5, 1880, in Brody, Galicia. Nothing is known about her life, her husband, whether she had children, or what she did for a living. She probably moved to Berlin in the 1920s, where she lived at Friedbergstrasse 26.

It could be that Leon Rebensaft, who may have been her nephew, moved in with her in the 1930s, since the death certificate issued after he was murdered at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp lists his address as Friedbergstrasse 11 (today 26).

Feige Rebensaft was deported to the Litzmannstadt ghetto on October 24, 1941, with the 2nd “Osttransport.” These deportations to the east began after the Soviet Union was invaded in the fall of 1941. During that fall, 7,034 Jews from Berlin alone were deported to the east.

ID cards were kept for the people interned in the Litzmannstadt ghetto. An ID card dated June 7, 1943, was issued to a woman named “Faiga Rebenzaft,” whose date of birth was given as May 1, 1885. Since there is no other Feige or Faiga Rebens(z)aft in the Holocaust databases, we can assume that this card belonged to Feige Rebensaft from Friedbergstrasse. A mistake may have been made when the birth year was recorded, or she may have told the issuing authority that she was younger. The card also lists her profession as “sales clerk” and says that she worked peeling vegetables in a kitchen in the ghetto.

According to a note in the margins of an index card in the files of the head of the Berlin-Brandenburg Regional Finance Office, in 1967 a man named Henry Reben had asked for information about the circumstances of Feige Rebensaft’s life and death. This was probably Heinz Rebensaft, born on March 21, 1914, who was able to emigrate and took the name Henry Reben in the United States. He died in 1998, and we were not able to locate any descendants.

Feige Rebensaft’s date of death is unknown.

Research and text: Prof. Tine Stein, Jan Lange

Leon Rebensaft

Leon Rebensaft was born on May 22, 1915, in Lemberg. It is not known when he came to Berlin. His death certificate of June 16, 1942, lists Friedbergstrasse 11 (today 26) as his address and “chauffeur” as his occupation. In 1938 he was still living with his mother, Fanny Rebensaft (née Zwerdlinger), at Linienstrasse 215. A sister of his, Dancia Czarlinski, lived at Wielandstrasse 38. Leon Rebensaft remained a Polish citizen.

In 1938 Leon Rebensaft was accused and convicted of having sold a stolen accordion and sentenced to 25 days in prison for receiving stolen goods. According to the records of the case, he had been unemployed since October 1937.

In the course of mounting persecution of Polish and stateless Jews after the war began, Leon Rebensaft was arrested on December 4, 1940, and taken to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. There he was ordered to be shot on May 28, 1942, at the age of only 26, along with 250 other Jews. These mass executions were Himmler’s retaliation for an arson attack on a Nazi anti-Communist propaganda exhibition by the resistance group led by Herbert Baum. The group that was shot was made up in part of Jews who had been arrested right after the attack and in part of prisoners from Sachsenhausen, one of whom was Leon Rebensaft.

Research and text: Prof. Tine Stein, Jan Lange

Friedbergstrasse 33

Bruno Landsberg

Bruno Landsberg was born in Berlin on June 25, 1872, as the son of Samuel Landsberg (born on March 22, 1829, in Bojanowo in the province of Posen) and his wife Johanna, née Hurwitz, (born on September 14, 1844, in Kelm, Russia). He had two sisters, Liesbeth (1866-1926) and Margarethe. His father died in Berlin on March 13, 1903, and his mother on September 1, 1934, at Friedbergstrasse 33. Both parents were buried in the Jewish Cemetery in Weissensee.

Bruno Landsberg was unmarried and childless, and was a traveling salesman by profession. He apparently lived in his mother’s apartment and inherited her share of the property at Friedbergstrasse 33 when she died. In the Berlin address books from 1936 to 1938, he is listed as a co-owner and property manager of the building.

His sister Margarethe, who was married to a lawyer, Dr. Julian Jacobsohn, was able to emigrate to the United States via Guatemala in March 1939; her daughter and son-in-law had already left for the States in 1938 and 1936. Bruno Landsberg stayed behind alone in Berlin.

On November 6, 1942, Bruno Landsberg was taken from Friedbergstrasse 33 and deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp with 99 other elderly victims on the 73rd “Alterstransport.”

Starting in 1941, the former garrison town of Theresienstadt became a transit camp for Jews from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. At the Wannsee Conference of January 20, 1942, Theresienstadt had been designated a “ghetto for the elderly,” but this designation was propaganda. In reality, the camp was part of the “final solution to the Jewish question” agreed on at the conference. With “Heimeinkaufsverträge,” contracts that promised housing, food, and medical care in the ghetto to Jewish veterans of World War I, the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) managed to steal the assets of the deportees. Despite the contracts, the people interned in the ghetto were crowded into barracks, given little food and water and inadequate medical care, and suffered from unbearable heat in the summer and bitter cold in the winter. In just a short time, thousands of these elderly people died of exhaustion, dysentery, and the loss of any will to live.

Bruno Landsberg died at the age of 70 on December 30, 1942, less than two months after arriving at the camp.

Research and text: Prof. Ulrich K. Preuß

Friedbergstrasse 34

Gustav Lewy

Gustav Lewy was born on February 14, 1867, in Dirschau, in the administrative district of Danzig. He moved to Berlin with his parents, Louis and Rebecca Bertha Lewy. He worked as a tradesman, and in 1899 he married Hulda Kallmann, who had been born in Wronke, near Posen, on May 7, 1869. Their daughter Tana was born on May 11, 1902, and their daughter Lane on August 6, 1904. Hulda Lewy did not work.

In the 1930s, the family lived at Friedbergstrasse 34; Gustav Lewy retired in 1939. In 1940, the building owner, a senior civil servant, evicted the family on the basis of the “Law concerning Jewish Tenants,” which was passed on April 30, 1939. By 1942 at the latest, the family lived in a crowded “Judenhaus” (Jewish house) at Droysenstrasse 18.

Hulda Lewy died on January 18, 1942.

At the end of May/beginning of June 1942, Gustav Lewy was arrested and taken to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. His prisoner number was 0422826, and he was incarcerated in Block 39. Starting in 1941, Jews were no longer taken to concentration camps in Germany, but deported to Eastern Europe instead. One possible explanation for Gustav Lewy’s arrest is the “hostage-taking” of Jews in Berlin on May 28/29, 1942, as retaliation for the attack on the Nazi propaganda exhibition “The Soviet Paradise” by a resistance group led by Herbert Baum. Since Jews were also involved in this act of resistance, 500 Jews were arrested, many of whom were immediately shot. Gustav Lewy was probably among the victims who were brought to Sachsenhausen. (The details of these arrests are still not completely known.)

Weakened by the conditions of his imprisonment, Gustav Lewy fell ill and died on June 12, 1942, at Sachsenhausen.

His daughters, Tana Stern and Lane Grünebaum, were later deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp and murdered.

Research and text: Evelyn Krause-Kerruth, Margret Haep-Lohmann

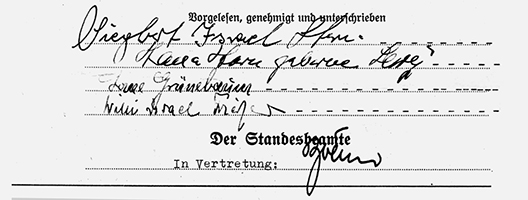

Tana Stern

Tana Stern was born on May 11, 1902, as the daughter of Gustav and Hulda Lewy. Her sister Lane was born on August 6, 1904, and both probably spent their childhood and adolescence in Berlin.

In the 1930s, Tana Stern lived with her parents and sister at Friedbergstrasse 34. In 1940, the building owner, a senior civil servant, evicted the family on the basis of the “Law concerning Jewish Tenants,” which was passed on April 30, 1939. By 1942 at the latest, the family lived in a “Judenhaus” (Jewish house) at Droysenstrasse 18.

Her mother, Hulda Lewy, died on January 18, 1942, and her father, Gustav Lewy, was arrested and taken to Sachsenhausen at the end of May/beginning of June 1942. Weakened by the conditions of his imprisonment, Gustav Lewy fell ill and died on June 12, 1942, in this concentration camp. Tana Stern’s sister, Lane Grünebaum, was deported on December 14, 1942, and murdered in Auschwitz.

On December 4, 1942, Tana Lewy married Siegbert Salomon Stern, a tradesman born on September 25, 1901, in Forst (Lausitz). They were divorced a month after they married.

During the 1930s, Siegbert Stern had owned a small business on Hausvogteiplatz where he made and sold women’s belts. He lived with his sister, Ilse Henriette Stern, at Helmstedter Strasse 23.

Like all Jews able to work, Siegbert and Tana Stern had to do forced labor. Tana Stern worked for the company Elektrolux, which had been making military equipment for the air force since 1939 on Oberlandstrasse at Tempelhof Airport, while Siegbert Stern worked at a shoe factory.

It had been clear since the beginning of November 1942 that all of the Jewish laborers working in the arms industry – who had been relatively safe until then – would soon be deported to Auschwitz. Siegbert Stern was arrested on February 28, 1943, in an operation called the “factory action” and deported to Auschwitz on March 3, 1943. He died in the camp hospital on April 3, 1943, after having done heavy labor in the Buna-Werke plant in Auschwitz.

Starting in January 1943, Tana Stern lived with the Bamberger family at Barbarossastrasse 60 in Schöneberg, in a “Judenwohnung” (Jewish apartment). Tana Stern and Erna Bamberger had met at Elektrolux, where they were both forced laborers.

Tana Stern was arrested on February 14, 1943, and held at the Grosse Hamburger strasse collection camp until being deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp on February 19, 1943.

She was murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau on March 10, 1943.

Research and text: Evelyn Krause-Kerruth, Margret Haep-Lohmann

Lane Grünebaum

Lane Grünebaum was born in Berlin on August 6, 1904, as the younger daughter of Gustav and Hulda Lewy. Her older sister Tana was born two years earlier on May 11, 1902. Both girls probably spent their childhood and adolescence in Berlin. In the 1930s, Lane Grünebaum lived with her parents and sister at Friedbergstrasse 34. We do not know what her profession was or how long she was able to pursue that profession during the years in which Jews were deprived of their rights.

In 1940, the building owner, a senior civil servant, evicted the family on the basis of the “Law concerning Jewish Tenants,” which was passed on April 30, 1939. By 1942 at the latest, the family lived in a crowded “Judenhaus” (Jewish house) at Droysenstrasse 18.

Probably around this time, Lane Lewy met and married Josef Grünebaum. Josef Grünebaum was born on October 21, 1902, in Franconia and was still living in Zwickau as of 1939. In Berlin he worked as a forced laborer for a demolition company; he, too, lived at Droysenstrasse 18.

Starting in 1940, Lane Grünebaum also had to perform forced labor until she was deported in 1942.

Her mother, Hulda Lewy, died on January 18, 1942, and her father, Gustav Lewy, was arrested and taken to Sachsenhausen at the end of May/beginning of June 1942. Weakened by the conditions of his imprisonment, Gustav Lewy fell ill and died on June 12, 1942, in this concentration camp.

Her sister, Tana Lewy, got married on December 4, 1942; Lane Grünebaum was her witness. Ten days later, on December 14, 1942, Lane and Josef Grünebaum were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The actual day on which they were murdered is unknown. Tana was murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau on March 10, 1943.

Research and text: Evelyn Krause-Kerruth, Margret Haep-Lohmann

Max Stern

Max Stern was born on June 3, 1879, in the Strehlen district in Silesia and moved to Berlin with his family when he was still a child.

After attending school at Berlin’s Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster, he first did a commercial apprenticeship in Frankfurt am Main and then moved to Switzerland, where his family now lived. He and his brother started a business selling postcards and art prints. Later, back in Berlin, the two brothers ran an art dealership.

Max Stern did military service in World War I. After the war, he opened a photography business on Rosenthaler strasse in Berlin-Mitte.

On May 14, 1919, Max Stern married Elisabeth Hannemann, who was not Jewish, and they moved into a four-room apartment at Friedbergstrasse 34. The couple had no children.

In the 1920s, Max Stern worked as an organizer and sales representative in AEG’s typewriter department. He was fired in 1933, and he and his wife had to support themselves by selling office supplies and renting out rooms in their apartment.

After the “Night of Broken Glass” in 1938, Max Stern was attacked on the street and taken to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. He was released in January 1939, by then seriously ill and suffering from constant pain from which he never recovered.

When the building owner, a senior civil servant, threatened to evict the Sterns for “Rassenschande” (“race pollution”), the couple filed for divorce in order to keep the apartment. They continued to live together at Friedbergstrasse 34 even after the divorce was finalized on February 21, 1939, but after another eviction threat, Max Stern was admitted to Berlin’s Jewish Hospital. Starting in the summer, he lived with a Jewish family on Kaiserdamm, where his wife visited and took care of him. They planned to have him move back to Friedbergstrasse.

On September 30, 1939, Max Stern collapsed on the street and died on the way to the hospital. His death was the result of the physical abuse he suffered at Sachsenhausen. He was buried at the Jewish Cemetery in Weissensee on October 8.

Research and text: Evelyn Krause-Kerruth, Margret Haep-Lohmann

Friedbergstrasse 41

Hermine Schwarz

Hermine Schwarz was born in Vienna on November 2, 1871. We do not know when or why she came to Berlin. She was unmarried and had no profession. Hermine Schwarz first lived in Berlin-Hohenschönhausen and later moved to Friedbergstrasse 41, where Max Morris lived with her as a subletter. Whether the two of them were related or were friends is unknown.

On January 13, 1942, Hermine Schwarz was first taken to the collection camp in the synagogue at Levetzowstrasse 7-8 and – although she was 71 years old – classified as “able to work.” On the same day, she was deported from Platform 17 of the Grunewald freight station on train Da 44 of the 8th “Osttransport” to the Riga ghetto, where she was murdered.

Research and text: Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Max Morris

Max Morris was born in Rehden near Graudenz in West Prussia on July 21, 1872. We do not know when or why he came to Berlin or what his profession was. Max Morris was unmarried and lived with Hermine Schwarz at Friedbergstrasse 41. Whether the two of them were related or were friends is unknown.

On January 13, 1942, Max Morris was first taken to the collection camp in the synagogue at Levetzowstrasse 7-8 and deported on the same day from Platform 17 of the Grunewald freight station on train Da 44 of the 8th “Osttransport” – along with other victims of National Socialist racial ideology: 993 from Berlin, 40 from Potsdam, and two from Duisburg – to the Riga ghetto, where he was murdered.

Research and text: Gisela Morel-Tiemann

Friedbergstrasse 47

Käthe Jacubowitz

Käthe Jacubowitz, née Richter, was born in Filehne in West Prussia on June 23, 1885. She married the tradesman Leopold Jacubowitz, who was born on November 8, 1872, in Lautenburg, which was also in West Prussia. They apparently had no children.

Käthe and Leopold Jacubowitz lived at Friedbergstrasse 47 until September 30, 1940, when they were forced to move to a “Judenwohnung” (Jewish apartment) at Essener strasse 24. There they were subletters in the apartment of Adolf Schwarz and occupied one and a half rooms in the front part of the building. According to the declaration of assets that they, like all Jews, were forced to submit, the Jacubowitzes did not have much in the way of property.

Käthe and Leopold Jacubowitz were taken from Essener strasse and deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto on July 27, 1942, with the 30th “Alterstransport.” Of the 100 elderly people deported on this train that day, 97 were murdered.

What happened to Käthe Jacubowitz is unknown. Her husband was killed in the Theresienstadt ghetto on March 21, 1944.

Research and text: Margit Robertz

Leopold Jacubowitz

Leopold Jacubowitz was born in Lautenburg in West Prussia on November 8, 1872. He was a tradesman and was married to Käthe Jacubowitz, née Richter, who was born on June 23, 1885, in Filehne, which was also in West Prussia. They apparently had no children.

Leopold and Käthe Jacubowitz lived at Friedbergstrasse 47 until September 30, 1940, when they were forced to move to a “Judenwohnung” (Jewish apartment) at Essener strasse 24. There they were subletters in the apartment of Adolf Schwarz and occupied one and a half rooms in the front part of the building. According to the declaration of assets that they, like all Jews, were forced to submit, the Jacubowitzes did not have much in the way of property.

Leopold Jacubowitz and his wife were taken from Essener strasse and deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto on July 27, 1942, with the 30th “Alterstransport.” Of the 100 elderly people deported on this train that day, 97 were murdered.

Leopold Jacubowitz was killed in the Theresienstadt ghetto on March 21, 1944.

Research and text: Margit Robertz

Contact

"Stolpersteine für die Friedbergstrasse" initiative

Editing team: Gisela Morel-Tiemann, Evelyn Krause-Kerruth, Carsten Molis

E-mail: fried.stolper@hotmail.com

If you would like to support the initiative’s work with a donation, please contact us at the e-mail address above.

Sources

We would like to thank the following people for their help:

Susi Bluth-Aronsfeld (died on August 28, 2013, Israel)

Michael Bluth (Gertrud Aronsfeld and the Unger family)

Svea Blumenthal (Rudolf and Vera Blumenthal)

General sources

Archives

Bundesarchiv:

Gedenkbuch Opfer der Verfolgung der Juden unter der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft in Deutschland 1933-1945

Ergänzungskarten für Angaben über Abstammung und Vorbildung der Volkszählung vom 17. Mai 1939

Landesarchiv Berlin

Landesamt für Bürger- und Ordnungsangelegenheiten, Berlin, Entschädigungsbehörde

Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv, Vermögensakten

Berliner Adressbücher 1920-1945

Transportlisten der Bezirksstelle Berlin, Nationalarchiv der USA, Sign. A3355.

Internationaler Suchdienst Arolsen

Centrum Judaicum Berlin

Jüdische Gemeinde Berlin

Jüdischer Friedhof Berlin-Weißensee

Memorials

Stiftung Brandenburgische Gedenkstätten

Gedenkstätte Sachsenhausen, Archiv

Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand

Haus der Wannseekonferenz

Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, Zentrale Datenbank der Namen der Holocaustopfer

Die Datenbank der Theresienstädter Häftlinge

Gedenkstätte und Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau

Kamp Westerbork, NL, Archiv

Museums

Museum Sachsenhausen

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, Holocaust survivors and victims database

Genealogy databases

ancestry.com, USA

geni.com, USA

jewishgen.org, USA

Secondary literature

Juden in Charlottenburg – Ein Gedenkbuch

Scheffler, Wolfgang: Zur Geschichte der Deportation jüdischer Bürger nach Riga 1941/1942. Vortrag

Sources on individuals

Friedbergstrasse Nr. 7: Dr. Julius and Martha Rothholz, Unger family, Gertrud Aronsfeld

BBF/DIPF/Archiv, Gutachterstelle des BIL – Personalkartei (personnel files) der Lehrer höherer Schulen Preußens; personnel file of Julius Rothholz

Kranzfelder, Ivo: Platschek, Hans Philipp. Article in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 20 (2001)

Platschek, Karl (“Carlos”): Survivor Story. In: The William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

Rothholz, Martha: Three letters from 1938 to Dr. Phillip Zenner. Archives & Special Collections, Ohio University

Heinz Joachim Unger: www.dokin.nl

Friedbergstrasse Nr. 26: Carl and Hildegard Levy

Grundbuchamt Charlottenburg

Friedbergstrasse 34: Gustav Lewy, Tana Stern

Standesamt Charlottenburg

Heimatmuseum Alt-Mariendorf

Stadtarchiv Forst (Lausitz)

Staatsarchiv Danzig

About this site

Responsible pursuant to § 5 of the German Telemedia Act (TMG):

Carsten Molis

Friedbergstrasse 47

14057 Berlin

Contact:

Tel.: +49 30 32 60 91 99

Fax: +49 30 32 60 91 98

E-mail: carstenmolis@aol.com

www.molis-consulting.de

Graphic design/Layout:

Denise van BeekProgramming:

With the kind support of op media - oliver plath media designExclusion of liability

The operator of this website is not liable for the content of the individual pages describing the fate of the people listed here. Those responsible for the content of these pages, who also hold copyright to them, are listed on the page itself.

Photo credits

Photo credits are given on the page where the photo appears. Background image: Denise van Beek

Liability for content

The greatest care was taken in compiling the content of this website. However, we cannot assume any liability for the correctness, completeness, or currency of the information on these pages. Pursuant to § 7, para 1 of the TMG, we as a service provider are legally responsible for our own content on these pages. Pursuant to §§ 8 to 10 of the TMG, however, we are not obligated to monitor third-party information provided or stored on our website or to search for violations of the law. Any obligation to remove or block the use of content pursuant to general laws shall remain unaffected. Our liability in such a case shall commence at the time we become aware of the violation in question, and we shall then promptly remove such content.

Liability for Links

Our website contains links to third-party websites. Because we have no influence on their content, we cannot assume any liability for such content. The content of these websites is the responsibility of the provider or operator of the website in question. We examined the linked sites for any possible infringements of the law at the time they were linked to ours, and did not identify any unlawful content at that time. Constant examination of the content of linked sites would constitute an unreasonable burden without concrete grounds for suspicion. Links will be promptly removed as soon as we become aware of any violations of the law.

Copyright

The content and works compiled by the website operator on these pages are subject to German copyright law. Reproduction, editing, distribution, and any use outside the limits of copyright are subject to the written consent of the respective author. Downloads and copies of these pages are permitted only for private, non-commercial use. In the case of material on this website that was not created by the operator, the copyright of third parties will be respected. Content by third parties is identified accordingly. However, if you should happen to notice a copyright violation, please let us know. We will remove the content in question promptly, once we become aware of any such violation.

Privacy protection

As a rule, it is possible to use our website without having to provide personal information. If personal information (such as your name, address, or e-mail address) is collected anywhere on this website, providing such information shall be voluntary (as far as possible). This information will not be given to third parties without your express permission. Please be aware that transmitting data via the Internet (e.g., by sending e-mails) entails inherent security risks. It is impossible to completely prevent unauthorized access by third parties. We expressly oppose the use of the contact data provided under “About this site” to send unsolicited advertising and informational material, and the operator of this website reserves the right to take legal action in the case of such unsolicited advertising (e.g., through spam).